How Seoul Emerged as a Key Art District for Asian Street Artists

Seoul occupies a distinctive place in contemporary street art culture. Unlike cities where urban art evolved primarily through graffiti or political murals, Seoul’s street scene developed at the intersection of youth culture, design, music, and nightlife. The result is an art district ecosystem that is informal, fast-moving, and deeply connected to public participation.

This article explores why Seoul became relevant for street artists, how neighborhoods like Hongdae function as cultural engines, and how early street practices such as wheatpaste and street vending influenced long-term artistic trajectories.

Seoul’s Urban Context and Visual Culture

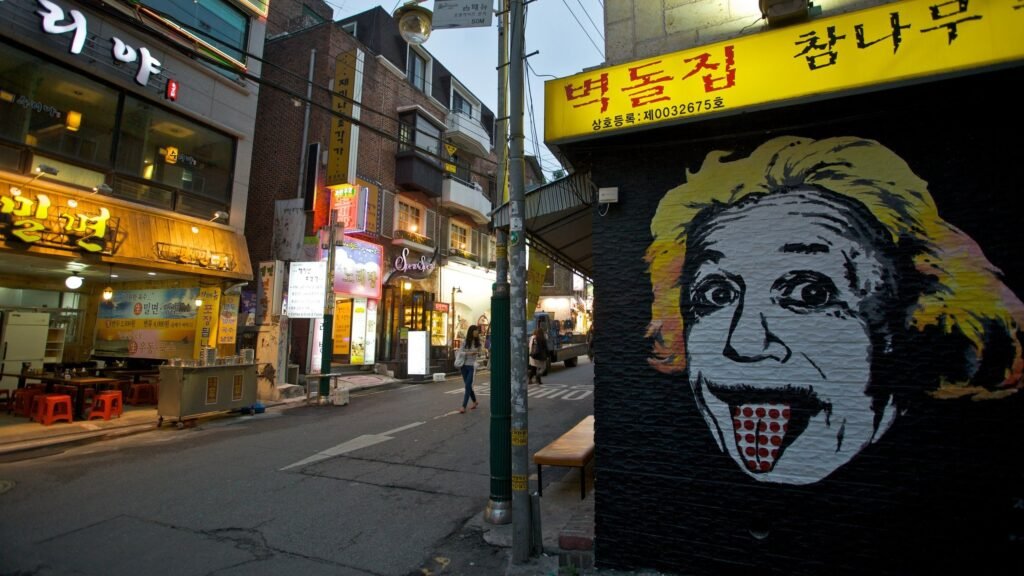

Seoul is a city defined by contrast. Hypermodern architecture exists alongside dense pedestrian neighborhoods. Technology-driven lifestyles coexist with strong street-level social interaction. This density creates constant visual competition; signage, fashion, music, and screens demand attention.

Street art in Seoul responds to this environment. To survive visually, it must be immediate, symbolic, and repeatable. This condition naturally aligns with street culture principles where recognition matters more than permanence.

Rather than emerging from protest alone, Seoul’s urban art grew from youth-driven creativity. Art became part of everyday nightlife, fashion, and movement.

Hongdae as a Cultural Art District

At the center of Seoul’s street culture is Hongdae, an area shaped by independent music, art schools, clubs, and informal commerce. Hongdae functions less like a curated art district and more like an open laboratory. Artists perform, sell, paste, and paint in direct contact with audiences. The street is not just a display surface; it is a testing ground. Works succeed or fail instantly based on public reaction. This dynamic makes Hongdae comparable, in different ways, to curated districts such as Wynwood Walls or decentralized scenes like Berlin. Each operates differently, but all function as entry points into global urban art conversations.

Street Commerce as Artistic Education

Seoul’s street art scene developed relatively recently compared with Western cities. Before the late 1980s, South Korea was a controlled state. In 1989, South Korea officially fully liberalized overseas travel for its citizens. Urban art in Korea was limited by strict anti-graffiti laws, and most public space art was legal murals, commissioned works or community projects rather than unsanctioned graffiti or paste-ups. Over recent decades however, neighborhoods with high youth presence became key sites where various forms of street art, including paste-ups, started appearing.

Another defining feature of Seoul’s street culture is it’s informal commerce. Selling art directly on the street is not peripheral; it is foundational. Night markets, pop-up stalls, and spontaneous displays blur the line between artist and audience. This environment teaches artists critical skills; visibility, adaptability, and communication. The street becomes a classroom where feedback is immediate and unfiltered.

For many artists, including TOKEBI (Bernal Aguilar), Seoul was a formative environment. During his years living as an expatriate in the city, TOKEBI began experimenting with wheatpaste as a medium, and in parallel also selling his skull-based creations printed on t-shirts directly on the streets of Hongdae, often late at night when pedestrian traffic reached its peak. This period constituted an early laboratory for understanding repetition, symbolism, and audience response, long before his work entered other contexts.

Because Seoul’s street art scene was underground for much of its development, street art often appeared informally, without formal recognition or documentation, as ephemeral works of public art or social commentary rather than established practices referenced in official histories.

Seoul’s Role in Global Urban Art

Seoul functions as a connector city. Artists move between Seoul, Berlin, and cities in the Americas, exchanging aesthetics and methods. This circulation reinforces the idea of urban art as a global cultural language rather than a local phenomenon.

Unlike cities defined by a single movement, Seoul absorbs influences rapidly and redistributes them through fashion, design, and digital culture. Street art here is not isolated; it is integrated into broader creative industries.

Art Districts Beyond Formal Recognition

Seoul challenges conventional definitions of art districts. Its relevance does not depend on large murals or institutional endorsement. Instead, it thrives on activity; street performance, vending, pasting, and repetition. This model contrasts with curated districts yet complements them. Seoul demonstrates that an art district can exist without fixed boundaries, sustained by participation rather than preservation. Below are three internationally recognized Korean artists strongly associated with street art, urban art, and contemporary visual culture. Each has contributed to Korea’s visibility within the global urban art conversation.

Jay Flow is a pioneering figure in Korean graffiti culture. Active since the early development of graffiti in South Korea, his work combines traditional graffiti lettering with contemporary mural practices. He played a key role in establishing graffiti as a legitimate urban art form in Korea and connecting the local scene with the global graffiti movement.

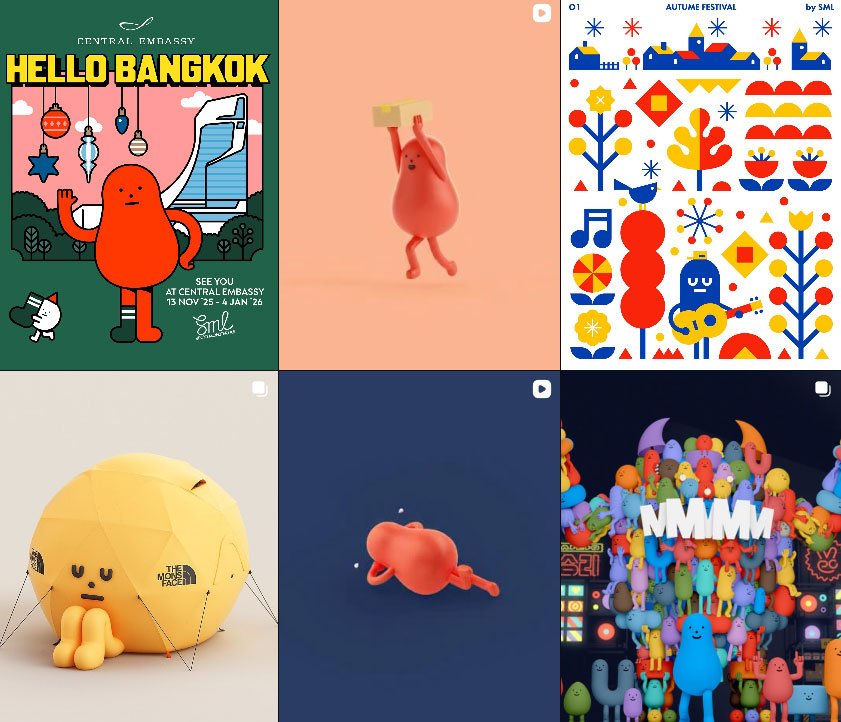

Sticky Monster Lab is one of South Korea’s most internationally visible urban art collectives. Their work blends street art, illustration, animation, and character design. While not strictly graffiti-based, their influence on contemporary urban art culture is significant, especially through large-scale murals, installations, and collaborations with global brands. They helped legitimize character-driven urban art from Korea on the international stage.

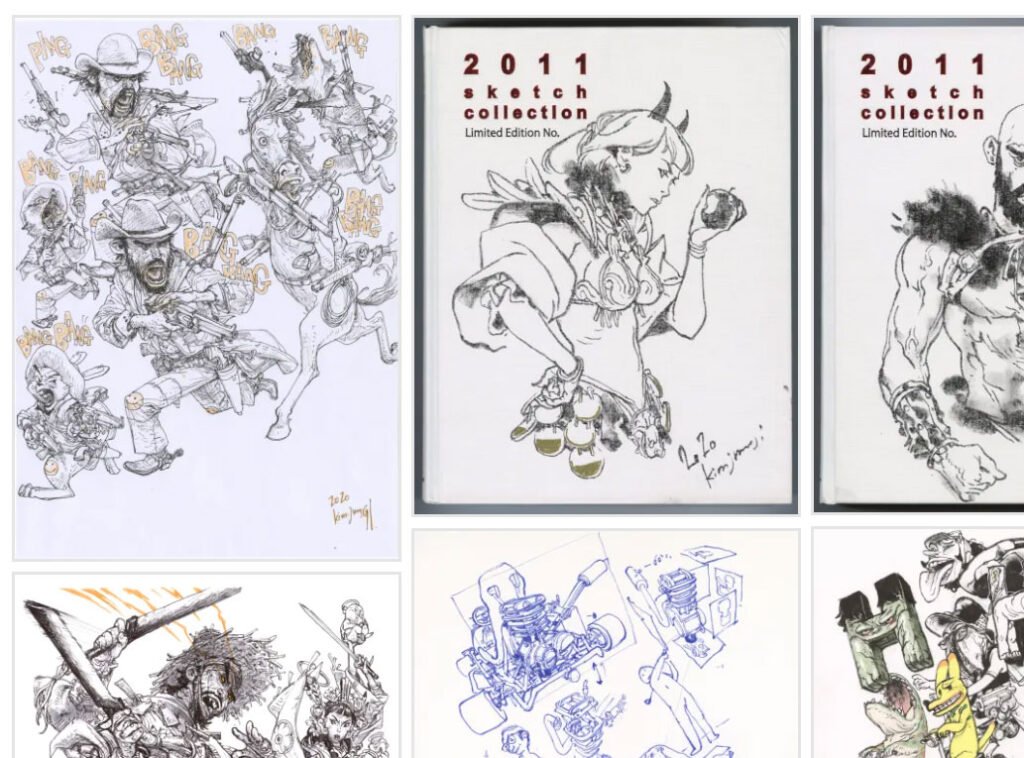

Although primarily known as an illustrator, Kim Jung Gi’s impact on street and urban art culture is profound. His large-scale live drawings and murals in public spaces blurred the line between illustration, muralism, and street performance. His ability to draw complex scenes from memory influenced an entire generation of urban and mural artists worldwide.

Repetition, Memory, and Street Presence

Repetition remains central to Seoul’s street art logic. Symbols appear on posters, clothing, stickers, and walls. Over time, these symbols become familiar markers of presence. This repetition connects Seoul’s street culture to broader discussions on how symbols gain meaning through recurrence. Identity in public space is not declared; it is reinforced. Seoul remains relevant because it is alive. It evolves nightly. Artists test ideas in real time, adapting to crowds, trends, and reactions. The city does not freeze street art into monuments; it allows it to circulate, disappear, and return. For artists shaped by street interaction, Seoul offers something rare; a place where art is not separated from life. It is sold, shared, pasted, and worn in the same space where it is created.

Seoul’s importance as an art district lies in its immediacy. Neighborhoods like Hongdae demonstrate how street culture, repetition, and symbolism form sustainable creative ecosystems. As long as Seoul continues to reward presence over permission and repetition over spectacle, it will remain a vital reference point in global street art culture.

Written by TOKEBI, an independent visual artist exploring urban aesthetics and contemporary mythologies.

SHARE IT: